Can alterations in the brain truly transform ordinary citizens into criminals? A groundbreaking study has revealed that damage to a specific area of the brain may indeed contribute to criminal or violent behavior.

A recent study, spearheaded by researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, is shedding light on the neurological underpinnings of violence and moral decision-making. The findings were published in Molecular Psychiatry.

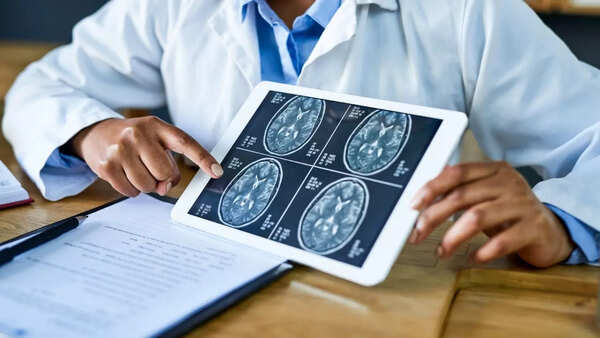

To investigate the correlation between brain injury and criminal behavior, researchers analyzed brain scans of individuals who began engaging in criminal activities following brain injuries resulting from strokes, tumors, or traumatic events.

These scans were compared with those of 706 individuals exhibiting other neurological symptoms like memory loss or depression. The results were compelling. The researchers discovered that damage to a specific brain pathway on the right side, known as the uncinate fasciculus, was a common factor among those displaying criminal behavior. This pattern was also observed in individuals who committed violent crimes.

Christopher M. Filley, MD, professor emeritus of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a co-author of the study, explained, "This part of the brain, the uncinate fasciculus, is a white matter pathway that serves as a cable connecting regions that govern emotion and decision-making. When that connection is disrupted on the right side, a person’s ability to regulate emotions and make moral choices may be severely impaired."

Isaiah Kletenik, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and lead author of the study, added, "While it is widely accepted that brain injury can lead to problems with memory or motor function, the role of the brain in guiding social behaviors like criminality is more controversial. It raises complex questions about culpability and free will."

Kletenik recounted his experience during behavioral neurology training at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, where he evaluated patients who began committing violent acts following the onset of brain tumors or degenerative diseases.

“These clinical cases prompted my curiosity into the brain basis of moral decision-making and led me to learn new network-based neuroimaging techniques at the Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School,” Kletenik stated.

To further validate the findings, the researchers conducted a comprehensive connectome analysis, utilizing a detailed map of brain region interconnections. The analysis confirmed that the right uncinate fasciculus was the neural pathway most consistently linked to criminal behavior.

Filley emphasized, “It wasn’t just any brain damage; it was damage in the location of this pathway. Our finding suggests that this specific connection may play a unique role in regulating behavior.”

The uncinate fasciculus connects brain regions associated with reward-based decision-making and those involved in processing emotions. Damage to this link, especially on the right side, can impair impulse control, the ability to anticipate consequences, and empathy, all of which can contribute to harmful or criminal actions.

The researchers also clarified that not everyone with this type of brain injury turns violent. However, damage to this tract may contribute to the new onset of criminal behavior after injury.

Filley stated, “This work could have real-world implications for both medicine and the law. Doctors may be able to better identify at-risk patients and offer effective early interventions. And courts might need to consider brain damage when evaluating criminal responsibility.”

Kletenik further noted that the study's findings raise critical ethical questions. "Should brain injury factor into how we judge criminal behavior? Causality in science is not defined in the same way as culpability in the eyes of the law. Still, our findings provide useful data that can help inform this discussion and contribute to our growing knowledge about how social behavior is mediated by the brain," Kletenik concluded.

Newer articles

Older articles

Earth's Spin Accelerating: Scientists Predict Potential 'Negative Leap Second' by 2029

Earth's Spin Accelerating: Scientists Predict Potential 'Negative Leap Second' by 2029

5 Subtle Signs of Cervical Cancer Women Often Miss

5 Subtle Signs of Cervical Cancer Women Often Miss

Hair Oil vs. Hair Serum: Choosing the Right Treatment for Your Hair Type

Hair Oil vs. Hair Serum: Choosing the Right Treatment for Your Hair Type

Steven Smith Targets Test Return After Unique Baseball Cage Recovery in New York

Steven Smith Targets Test Return After Unique Baseball Cage Recovery in New York

Bollywood's Enduring Fascination with Indian Mythology: From Ramayana to Modern Blockbusters

Bollywood's Enduring Fascination with Indian Mythology: From Ramayana to Modern Blockbusters

Liver Disease: 5 Subtle Warning Signs You Shouldn't Ignore

Liver Disease: 5 Subtle Warning Signs You Shouldn't Ignore

Heart Attack Warning: Key Signs That Can Appear Weeks in Advance

Heart Attack Warning: Key Signs That Can Appear Weeks in Advance

New Zealand Announces Packed Home Cricket Schedule Featuring Australia, England, West Indies, and South Africa

New Zealand Announces Packed Home Cricket Schedule Featuring Australia, England, West Indies, and South Africa

Wimbledon Upset: Bhambri & Galloway's Doubles Run Halted in Tiebreak Thriller

Wimbledon Upset: Bhambri & Galloway's Doubles Run Halted in Tiebreak Thriller

Daren Sammy Fined, Receives Demerit Point for Third Umpire Criticism After Test Match

Daren Sammy Fined, Receives Demerit Point for Third Umpire Criticism After Test Match